My April 2023 On failed IT projects post did not address the political aspects of large scale IT system acquisition’s. The post is inspired by Dr. Brenda Forman’s chapter on the political challenge found in the book The Art of System Architecting, third edition, a book that is highly recommended.

The book addresses architecting of systems, and since a firms information technology, it be in the private or public sector is a system the systems architecting approach is applicable. For information technology to make any sense its structure must support the firm’s overall mission.

Politics as design factor

The bottom line is: If the politics don’t fly, the system never will. This is the case for any kind of system or technology program that require government funding. From a Norwegian perspective the National Transport Plan is a good example. Projects are moved up and down dependent of political climate. No project on the plan is safe before the funding is in place.

Architects must be able to think in political terms. According to Dr. Forman this mean to understand that political processes follows an entirely different logic than the logic applied by scientists and engineers. Scientists and engineers are trained to marshal their facts and proceed from facts to conclusion.

Political thinking is different, it do not depend on logical proof, but on past experience, negotiation, compromise, and perceptions. Proof is the matter of having the votes. If the majority of votes can be mustered in the parliament the project has been judged to be worthy, useful and beneficial for the nation.

Mustering the votes depends only in part of engineering or technological merit. These are important, but to get the votes on a regular basis depends more on jobs and revenues in electoral districts than technological excellence. It might be more important for an elected representative to have a project that keep local construction contractors engaged for the next five years than the value from the traffic on the road when its completed.

To help architects navigate the rocky political landscape the following heuristics or as they are called in the book, The facts of life:

- Politics, not technology, sets the limits of what technology is allowed to achieve.

- Cost rules.

- A strong, coherent constituency is essential.

- Technical problems become political problems.

- The best engineering solution are not necessarily the best political solution.

Another observation is that political visions don’t fly without feasible technology and adequate funding. Example: In 2007 Norwegian prime minister Jens Stoltenberg uttered the following in his new year’s speech:

Our vision is that within 7 years we will have in place the technology that make it possible to capture carbon from a power plant. This will be an important break through for Norway and when we succeed the world will follow. This is a big project for the country. It’s our moon landing.

Sixteen years later; the technology does not exist and nobody talks about it. In the end there were no constituency, no funding and no politics to make it happen. The problem with such political dreaming is that it diverge effort and resources from things that could have been done, the small steps of improvement that over time could make a difference.

More troublesome are funded initiatives where the political accepted solution does not solve the operational problem at hand. My first encounter with such situation was back in 1990. A part of Norwegian government should spend a billion NOK (a heck of a lot of money) on computers without having a clue about the software to be run on those computers.

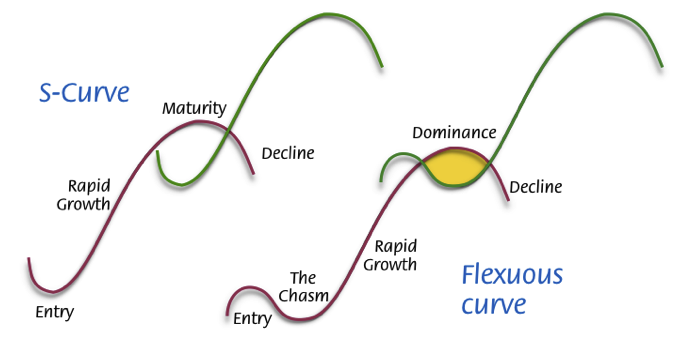

Enterprise information systems find themselves in an ill-structured and even complex problem world. Ill-structured problems are problems where the users don’t understand their needs before they see a solution. Complex problems implies that its deduct a solution from an analytical process. The only practical way to solve such problems is by experimentation. More on that can be found here.

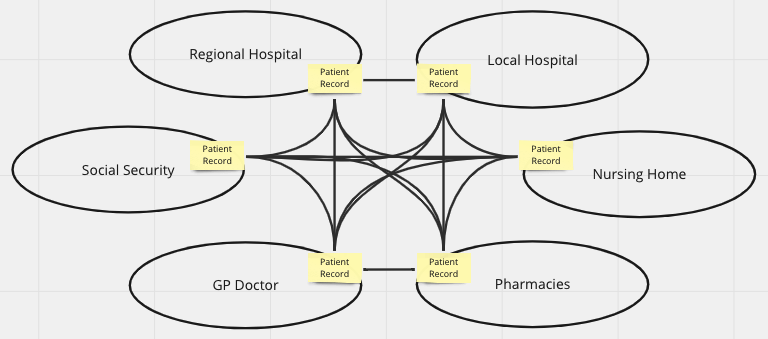

Systems architecting in political sensitive environments is an act of balancing conflicting complex systems. Political processes are complex in their own way and the same said about the operational context shown in figure 1 below.

Be aware that the end-users who live their lives in the operational context are not the same as the client paying for the solution in the political context. This is definitively the case in the public sector and its often the case in larger enterprises. To showcase the point lets explore a real world case that has run into trouble.

Case

Helseplattformen, is a large scale, highly complex health care IT project that according to the press suffers from cost overruns, delays and severe quality issues. Helseplattformen decided to acquire a commercial product from Epic Systems for what under any circumstance is a ambitious functional scope. A shared patient record across hospitals, general practitioners, specialists and municipal institutions in one of Norway’s health regions.

Reported problems included lost data, record lockings, cumbersome user interfaces and general instability, all leading to patient safety concerns. The fact that users in Denmark, UK and Finland had faced severe problems priory to the Norwegian acquisition make the situation even more dire. It shows that political processes might be ignorant to the facts on the ground. As the old proverb states:

Wise men learn from other mens mistakes, fools from their own.

The timeline (below) tell a story about a classical waterfall approach where potential issues are pushed to the end of the project, to first use when the cost of change is at its highest.

- 2015 – pre-project started

- 2017 – acquisition project started

- 2019 – contract signed with Epic Systems after tendering

- 2020 – lab module implemented but postponed due to Covid-19 pandemic

- 2021 – municipalities joining after political decisions

- 2022 – first use set to April, problems materialise

- 2023 – problems continue

The project stand out as a schoolbook example of how to fail, leading to the question what could have been done differently? Firstly, capture the essence of the problem in a context map (figure 2) and develop a firm problem statement. Secondly develop alternative options and assess them. Finally, choose the best option, typically the one that is least intrusive and risky to implement.

Assessment

Given that electronic health care records has been used for decades, all parties have working solutions today. The problem on the table is to create a EPJ that is shared across all parties. Such EPJ can be achieved in two principal ways.

- Acquire a new integrated system and enforce it on all parties

- Isolate the shared EPJ and integrate applications using API’s

Helseplattformen opted for alternative #1 by choosing an integrated solution from a vendor. Alternative #2 can be realised in two principle ways. By using a federated model according to the EU Data Spaces approach, or by using a centralised model according to the library model. Alternative #1 is tightly coupled and intrusive. Alternative #2 is loosely coupled and nonintrusive.

It is understandable that an integrated system from one vendor looks tempting for decision makers. From 35000 feet Epic Systems with a 78% US market share feels as a safe bet, but transporting a product made in one operational context to a complete new context driven by a complete different vision is most often a painful exercise. The only available approach to dig out the differences between is by paid up-front testing and evaluation of the product before any decision is made.

Products

Products, commercial or open-source is the key to cost efficient realisation of enterprise information systems. Products come in three forms. Large scale integrated products as Epic Systems and SAP. End user productivity tools such as MS Office and Google Docs, and technical components, libraries that are used by developers, they being in the enterprise or in the product space.

The crux with any product is the context that created them in the first place. A product developed for a specific context might be very hard to transport to a similar context in a new market. The larger and complex the product is, the worse it becomes. Therefore the only practical approach is to test before any decision is made. This is time consuming and expensive, but there are no short cuts when dealing with the complexity of mission critical enterprise information systems.

Conclusion

Politics rule information system acquisition processes and the only way to balance out political ambitions with operational excellence is systems architecting. Helseplattformen shows that enterprises need to strengthen their information technology system architecting capability and make it part of their business strategy function. As digitalisation become more and more important the need for digital savvy board members become evident.

Enterprise architects must move out of IT and start serving the business. To do so the enterprise architects must develop design skills and master richer modelling tools and approaches as described in my previous blog post on Object-Oriented Enterprise Architecting and in the next post titled on the essence of system design. It also mean to to work the political and technical realms equally.

An to help us remember why up-front systems architecting is important, lets quote Plato, 400BC.

All serious mistakes are made in the first day.

If the assumptions are wrong, the result ……