Change management is used as a collective term for all approaches to prepare, support, and help individuals, teams and organisations to change. I was challenged by a colleague to put forward my thoughts after she had read my previous post on digitalisation as a complex undertaking.

Change implies that something go from one state to another as water during its phase shifts from ice to floating to gas. Change management boils down to the management of the phase shifts, the transitions, the in between’s than the end states. How difficult this can be can be tested at home by boiling milk. Be prepared to clean up or pay attention to what takes place in the kettle.

The history of change management goes back to Kurt Lewin‘s work on group dynamics and change processes in the first half of the 20th century. At the time of his death in 1947, Lewin was seen as on of the foremost psychologist’s of his day. Today is Lewin best known for his three step change-model, also known as the unfreeze-change-refreeze using using an ice block as metaphor (fig. 1).

The challenge with this model is that enterprises pay to much attention on the as-is and the to-be, while ignoring that success or failure is down to the nature of the phase shifts themselves. How this take place is best illustrated by the anatomy of a typical enterprise change process:

- A problem or assumed short coming has been identified and the board of directors establish a project that is tasked to find solutions and propose alternative course(s) of actions.

- The board of directors decides to implement one of the proposed solutions and kicks off an implementation project tasked to implement the recommended changes.

- The implementation project create new organisational units, move people around while people do as best they can to make the wheels turn around.

I know I am tabloid here, but the most important takeaway is that such plan driven approaches does not work. The documentation is overwhelming, and still enterprises stick to the practice. What has proved to work are initiatives founded on lean and agile principles, principles that take into account that the challenge is the transition, not the end states.

Timing change

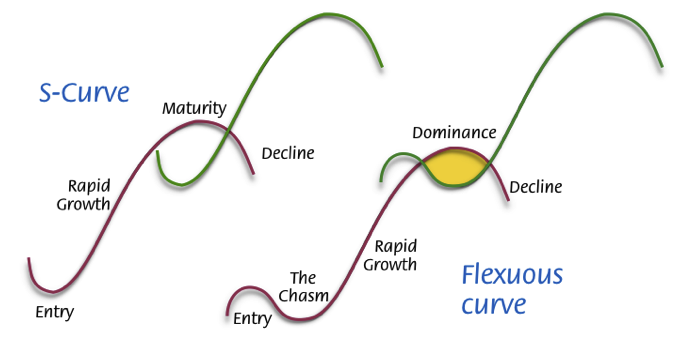

One reason old practices stick for to long can be found in Clayton Christensen work on disruptive innovation and product lifecycles where a product follows overlapping S-curves. Enterprises with profitable products are almost resilient to change. How Apple’s iPhone knocked Nokia out of business is one good example. Same is how the minicomputer industry was eradicated by the micro-processor in 1989-91. What was perceived as a healthy industry was gone in 18 months.

Dave Snowden has taken this understanding to a new level with his flexuous curves and the liminal moment (the yellow zone in figure 2) that marks the opportunity window. It shows that the change window is when your product is dominating. This is also a reason why changing is so hard.

Many enterprises stick to old practice despite that the evidence for change is overwhelming. This does not stop with products, but is applicable to work practices as well.

Leading change is hard

Disruptive innovation and flexuous curves can help us to better understand why and when change might be favourable, but they offer no help when it come to leading change efforts. Carl von Clausewitz might be one of the first who put words on the hardship of change in context of a complex system in his seminal 1832 book On War where he state:

“Everything is simple in war, but the simplest thing is difficult. These difficulties accumulate and produce a friction, which no man can imagine exactly who has not seen war.”

War, or battle to use a word that is more representative of 19th century reality can be understood as the dynamic state transition from pre-battle to post-battle that consists of timed and coordinated movements and counter movements of competing agents (armies). The competition ends when one or both sides have had enough. Each force being a interlinked hierarchical network of units built from individual agents and equipment.

There are two main takeaways from the war analogy.

- That business and change processes can be understood as timed and coordinated movements of resources and therefore face “friction”. Today we would not talk so much about friction but that businesses and enterprises are examples of complex systems.

- That the Prussian general staff under the command of General Helmuth von Moltke developed a new leadership style called mission command that is still used, a leadership style that emphasis subordinates to make decisions based on local circumstance in their strive for fulfilling the superiors intent. Stephen Bungay explains how these principles are relevant and can be repurposed for business in his book The art of Action.

To conclude, leading change processes is hard because they come with friction (things does not work out in practice as planned) and need a different leadership style than bureaucratic top down linear plans to succeed. This also challenge the way leaders are identified and trained.

An individuals leadership practice is an emerging property that is shaped by the context, and therefore can’t be copied. This breaks with the idea that a good leader can lead anything. This mean that its most likely different personalities that succeeds in operational contexts versus say a product development context. As individuals climb the corporate leadership stair this become crucial. To put an individual who have excelled in one context believing that he/she will succeed in a completely different context is dangerous.

How to succeed with change

The literature is crystal clear on how to succeed with change processes. Initiatives that empower individuals to drive change as activists, initiatives where individuals are invited to contribute, and initiatives that move from managed to organic has the best probability to succeed.

To move from managed to organic is most likely the most important of the three. Kurt Lewin’s three step change model still guides how leaders think about change, the problem being that there is no room to be frozen any more. According to McKinsey we need permanent slush that enables constant experimentation with new operating models, business models and management models, adopting the practices required when dealing with complex systems.

A complex system has no linear relationships between causes and effects and can’t be managed by linear measures. This leaves us with three principles as pointed out here:

- Initiating and monitoring micro-nudges, lots of small projects rather than one big project so that success and failure are both (non-ironically) opportunities

- Understanding where we are, and starting journeys with a sense of direction rather than abstract goals

- Understanding, and working with propensities and dispositions, managing both so that the things you desire have a lower energy cost than the things you don’t

Be also aware that its the alternatives with lowest energy cost that will win in the long run. Thats the reason point #3 is so important. We need to make what we will like to see more off cheaper than what we will like to see less off. These things must be anchored in the stories or narratives told by those who experience the existing reality and who in the end owns and lives with the changes.

Summing up, literature is crystal clear on what is the best way to approach change process. It boils down to knowing where you are, move in small steps and maintain a direction. Given the facts, why do enterprises stick to their old failed practices. To answer that question we must address some of the counter forces in play.

Counter forces

Counter forces come in many facets.

- Old habits are hard to change, as everybody knows who have tried to change a undesired behaviour. Enterprises are structures with internal friction and change resistance that take many forms. Not invented here might be one. Short term energy expenditure might be another.

- Lewin’s original model is linear, easy to grasp and leave senior leadership with the illusion that change is a final game that can be managed top down. I personally think it feels better from an ego’s point of view as well. Last but not least, its an easier sell for management consultancies providing case studies and best practice.

- Procurement processes. Many change processes related to introducing new digital capabilities involves procurement of new technology. Procurement processes require that you know what you need. One thing is to buy 100 car’s or 5000 meter with drill pipes. Digitalising a business process something completely different.

- Perceived senior management risk. Executives seek ways to reduce the perceived risk. One such way is to have contract. In the 1980ties nobody was fired for having signed on with IBM. My theory is that this boils down to psychology. Late sports psychology professor Willy Railo stated back in the 1980ties that “you don’t dare to win if you don’t dare to loose”. In other words its the fear of failure that trigger the behaviour that leads to failure.

- Approaching business as a finite game. Business and change processes are infinite games, but due to various factors leaders behave as their finite. A finite game is a game with fixed rules and time (football). An infinite game is a game that never ends and enterprises that acknowledge that their in it for the long run will benefit. To learn more check out this link. The main problem might be that funding might be finite as in the case of public sector initiatives that are run by budget allocation.

As we can read, there are many factors and counter forces in play. Some of these are most likely unconscious such as fear, others boils down to ignorance and laziness.

Synthesis

Change management has been with us for a while and literature is clear on what it take to succeed with change. Experiments, involvement, empowerment, small steps, continuous adjustments based on feedback and so om.

Despite this many enterprises stick to plan based approaches with failure in the end. There are many forces that leads to this, one being the finite nature of budgets, and particularly budgets that are managed by political processes.

To me this is at the stage where we know what to do, so its just go do it in ways we know work. Adapt agile practice and begin navigate the maze.

Two recommended readings are the EU field guide on crisis management and this article on Safety Interventions in an energy company. Teaser provided from it’s abstract

The paper describes a case study carried out in an electric utility organization to address

safety issues. The organization experiences a less than satisfactory safety performance

record despite nurturing a culture oriented to incident prevention. The theoretical basis of the

intervention lies in naturalistic sense-making and draws primarily on insights from the

cognitive sciences and the science of complex adaptive systems.

Data collection was carried out through stories as told by the field workers. Stories are a

preferred method compared to conventional questionnaires or surveys because they allow a

richer description of complex issues and eliminate the interviewer‟s bias hidden behind

explicit questions.

The analysis identified several issues that were then classified into different domains (Simple,

Complicated, Complex, Chaotic) as defined by a Sense-Making framework approach.

The approach enables Management to rationalize its return on investments in safety. In

particular, the intervention helps to explain why some implemented safety solutions

emanating from a near-miss or an accident investigation can produce a counterproductive

impact.

Lastly, the paper suggests how issues must be resolved differently according to the domain

they belong to.

Next post will be on failed IT projects.