Object-Orientation

Object-orientation a.k.a object-oriented thinking / modelling / programming is a way to explore real world complexity by turning real world elements into interacting “objects”. A restaurant, as an example can be modelled as a set of interacting objects representing concepts such as guests, tables, waiters, cooks, orders, bills, dishes, payments and so on. Object-oriented modelling can be conducted by rudimentary tools as as illustrated in figure 1.

Object-orientation goes back to the late 1950ties, but was first made available for broader usage with the Simula programming language in the mid 1960ties. Simula inspired new object oriented languages such as Smaltalk, C++, Java and many more.

Object-oriented programming lead to the development of object-oriented analysis and design, and more formal and powerful modelling techniques and languages such as UML (Unified Modelling Language), SYSML, ArchiMate and AKM (Active Knowledge Modelling) to mention a few. It can also be argued that EventStorming, a collaborative workshop technique is object oriented.

On the dark side, object-orientation does not protect agains poor practice. Poor design practice leads typically to tightly coupled systems, systems that become expensive or even impossible to adapt and enhance as technology and business change.

Design Patterns

Design patterns is one way to enhance design practice by provision of tangible abstractions and concepts that help practitioners to create more healthy structures. Patterns originate from civil architecture and is attributed to Christopher Alexander and his work on pattern languages for buildings and cities.

The Gang of Four (GoF) 1995 book Design Patterns – Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software was the first book that introduced patterns for object-oriented software development. The book is still relevant and highly recommended as an introduction to patterns.

Another seminal book that embrace patterns is Eric Evans 2003 book Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software. Eric argues that business problems are inherently complex, ambiguous and often wicked, and therefor must the development team spend more time on exploring domain concepts, and to express and test them in running code as fast as possible to learn.

Eric argues also for the importance of a common language in the team, the ubiquitous language, a language that embraces both domain and technical concepts. OrderRepository is an example of such language that make equally sense for subject matter experts and developers alike. It enables conversations like: orders are stored in the order repository and the order repository provides a function for creating and finding orders.

EventStorming is framed around the discovery and capture of three design patterns: Commands, DomainEvents and Aggregates as illustrated by figure 2.

The model reads that the doctor diagnoses the patient and add the diagnosis to the patient record. Then a treatment is prescribed, before the effects are checked at a later stage. EventStorming begins with capturing the capturing the events, and from them the commands and aggregates are derived.

There are particularly three software design patterns that I think should be part of every enterprise architects toolbox.

- Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) separates read operations from write operations enabling a clearer thinking on what those things mean in our architecture. Data Mesh is not possible without CQRS.

- Data Mesh is an architectural approach to manage operational and analytical data as products. Its enabled by CQRS and it comes with its own suppleness.

- Event Sourcing is based on storing changes as independent events. Bank accounts works this way as each deposit and withdrawal are stored as a a sequence of events, enabling the account to answer what was my deposits on a particular date back in time. Event Sourcing should not be conflated with Event Storming which is a workshop methodology.

The motivation behind the claim is that these patterns shape the architecture and the architects thinking. By knowing them the architect can make rational judgments with respect to their relevance in a given context.

Enterprise Architecting

Enterprise architects have used object-oriented concepts for years taking advantage of modelling languages such as UML, ArchiMate and others. Architects with interest and understanding of agile methodologies might also have explored EventStorming workshop techniques.

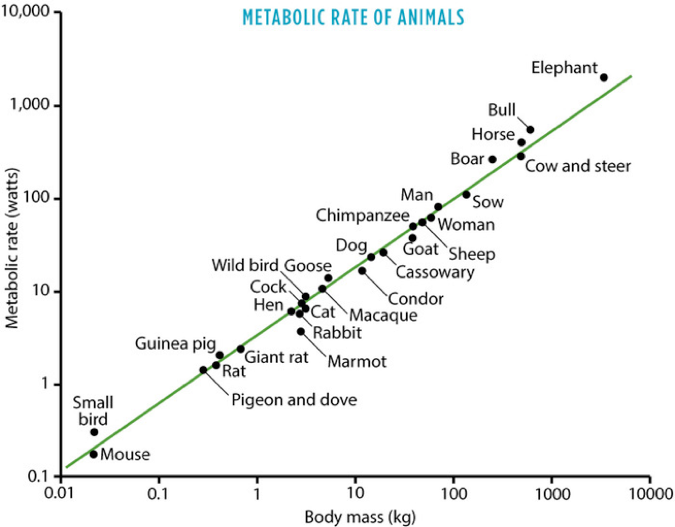

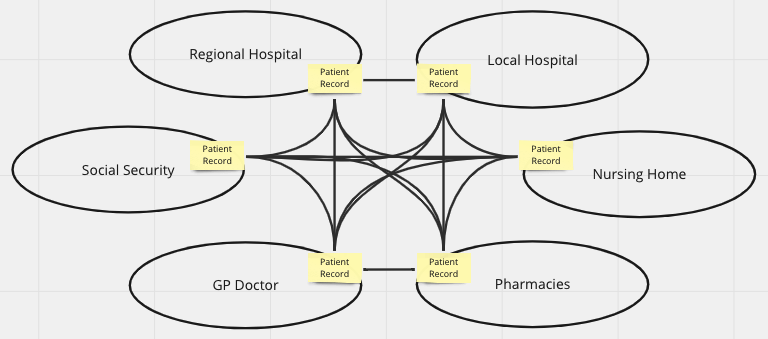

Independent of technical tooling enterprise architects face a growing challenge as enterprises digitalise their operating and business models. Take our healthcare model and scale it to a hospital or include multiple hospitals, the primary health services and elder care. In such environment you will have solutions from multiple vendors, solutions from different technical generations, and solutions that are outside your own control. Add then that sector is political sensitive and full of conflicting interests.

The catch being that this is not unique for healthcare but is the nature of the real world. Real world business problems are most often wicked or complex. Scaling up forces architects to slice the problem space into useful modules that can be managed independently. Such slicing must be done with care as coupling and lack of cohesion will haunt the chosen architecture.

The architectural crux is to get the slicing right. Sometimes this is easy as system boundaries follows natural boundaries in the domain. But this is not always the case as many enterprises have ended up with dysfunctional structures that leads to fragile and error prone handovers. Handover of patient information in the healthcare sector is a good example. The catch is that handovers are everywhere and its effects are loss of critical information and rework.

Strategic Design

Domain Driven Design offers a technique that help us model the slicing of a large model called Bounded Context and Context Mapping. Applied on our healthcare example we can create something like the diagram in figure 3.

Bounded Context are organised into a Context Map that captures the relationships between various bounded context. Adding to the complexity, each bounded context might need access to different aspects of the patient record. Example, pharmacies have no need for individual food constraints that are relevant for nursing homes and hospitals.

Making this even complex is the fact that all these contexts can be further decomposed as in figure 4. Add to this that in the case of an individual patient, specialists from different contexts need to collaborate to decide upon the path forward. It’s normal for surgeons, radiologists and oncologists to discuss a x-ray image of a tumor. Such trans-discipline collaboration is critical for problem solving, and its in these interactions balanced solutions to hard problems are shaped.

Figure 5 present two architectural alternatives, distributed and centralised. In the distributed architecture each bounded contexts is free to have whatever system they find useful as long as they are able to send and receive patient record update messages (events).

In the centralised architecture a new shared bounded context that manages the patient record has been introduced and the “operational” contexts accesses the shared and centralised record management system. Which one of those alternatives are “best” boils down to tradeoffs. Both come with strengths and weaknesses.

What matters is how we choose to pursue implementation. The crux i distributed architectures boils down to message standardisation and the establishment of a transport mechanisms. Centralised architecture can be realised in two principle ways.

- By using an old school integrated application with user interfaces and a shared database. Then force everybody to use the same solution. Integrated means tight coupling of user interfaces and the underpinning data / domain model into something that is deployed as one chunk.

- By developing a loosely coupled application or platform based on API’s that can be adapted to changing needs. Loos coupling means that the data management part – the record keeping is separated from end user tools along the lines described here.

Making the wrong choice here is most likely catastrophic, but beaware that all alternatives comes with strengths and weaknesses. To understand the alternatives feasibility a bottom-up tactical architecting endeavour is needed. Such endeavour should take advantage of battle proven patterns and design heuristics. In the end a claims based SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis might prove its weight in gold.

Tactical Design

Tactical design implies to dig into what users do, what information they need for doing what they do and to develop the information backbone that shapes the sector’s body of knowledge. Evaluation of implementation alternatives require tactical level design models as the devil is in the details.

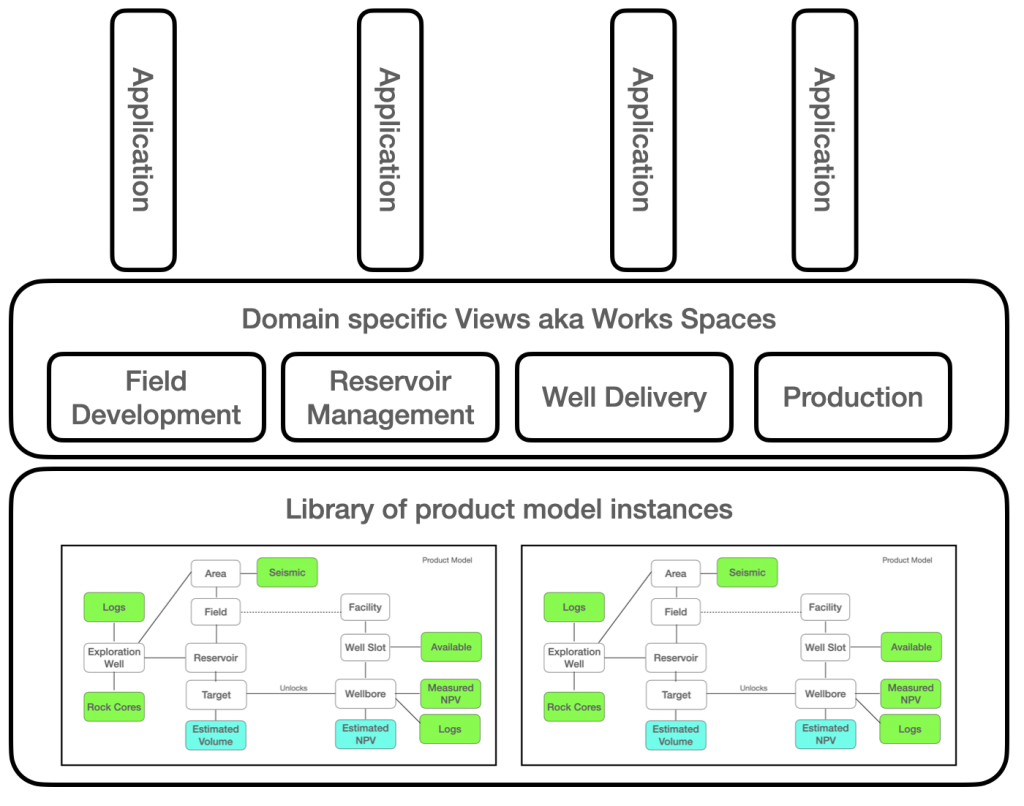

Tactical design is best explained using a practical example taking advantage of the capabilities provided by the AKM (Active Knowledge Management ) modelling approach. What make AKM different from other methods and tools is its dynamic meta models. The example model in figure 6 exploits the IRTV (Information, Roles, Tasks and Views) meta model. A deep dive in AKM modelling and meta-modelling will be addressed later.

The example builds on our healthcare case, and the purpose is to highlight the main modelling constructs, their usage and their contribution to the model as a tool for enlightened discussions, and future tradeoff analysis.

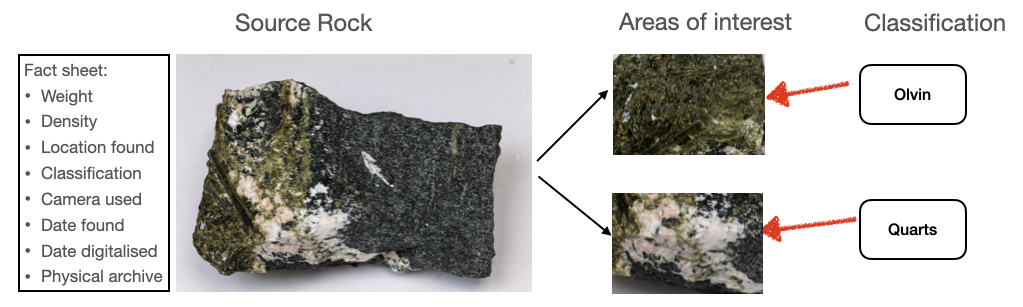

Healthcare can be thought of as stories about patients, diseases and treatments and that is what we will try to demonstrate by our toy model. Take note of the fact that some Information datatypes and Views have suggested types that can be used to create a richer and more domain specific language.

Be aware that diseases might have multiple treatments, and that a treatment can be applicable for more than one disease. This is by the way a good example of the “muddiness” of the real world where everything one way or the other is entangled.

The model in figure 6 captures two stories. The first story present a patient consultation session where the GP diagnoses a patient and updates the patient’s medical record. The second story shows how a researcher updates the treatment protocol.

At this point the sharp-eyed should be able to discover a pattern, and for those who don’t please read Reinventing the Library before you start studying figure 7 below. Here the model from figure 6 is restructured and simplified so the key points can be highlighted.

Firstly, the sector’s body of knowledge is structured around three concepts that are managed in a “library”. Such library could of cause be extended to include infrastructure components such as hospitals, caring homes, and even staffing. It all depends on what questions the enterprise want to answer and accumulate knowledge about.

Secondly, the design of functional domains by grouping related tasks into what DDD defines as bounded contexts. This design task should be guided by the key design heuristic; maximise cohesion, minimise coupling while reflecting over what can be turned into independent deployable’s if the architecture should take physical form as software applications.

Lastly, views as the key to loose coupling and as artefacts that need to be rigorously designed. Views are the providers of what AKM call workspaces. The model above contain two types of views. The first type is used to separate roles from tasks within a bounded context. This view is typically visual and interactive in nature as its designed to support humans. For those familiar with multi-agent design such view could be seen as an agents environment as explained here.

The second type of view are those that bridges between cohesive functional domains and the underpinning library. These views can also be used to create interaction between operational bounded contexts as can be seen in the case of the Diseases View in figure 7.

View would benefit from being designed according to the CQRS pattern, basically separating commands from Queries as shown in figure 8. In addition to queries and commands can views be the home for transformation, event processing and communication. In a software context views exposes domain specific API’s, they represents bounded contexts and they can be deployed independently as architectural quanta’s. Again the sharp-eyed should see that views might be the key for those who want to think in terms of data mesh and data products. A data-mesh boils down to transforming data so the data can be served to fit the consumers needs.

For those of you who are still here a couple of words about knowledge and the theoretical framework that motivated this post – constructor theory.

Constructor theory

Constructor theory or the science of can and can’t is a rather new theory in theoretical physics developed by David Deutch and later Chiara Marletto at the University of Oxford. The essence of constructor theory is that physical laws can be extended to cover what transformations are possible or not. This implies that Physics can be used to define concepts such as information and knowledge.

A constructor is a “machine” that can perform transformations in a repetitive way and to do that transformation it needs a “recipe”. A factory that create airplanes or cars are examples of constructors. Its the institutionalised knowledge in those entities that make it possible to mass produce samples over time with quality.

If we now revisit figure 7 and 8 it should be obvious that what we have architected could be understood as constructors. An that should not come as a surprise since constructor theory defines information by using two counterfactuals; the possibility of copying and of flipping (change state). Knowledge is defined as self preserving information.

My advice to enterprise architects is to read The science of can and can’t – enjoy as it is the perfect vacation companion.